Four generations of the Rovera family have dedicated themselves to the making of pipes.

Millions of hours of experience, together with a deeply emotional commitment to the craft,

have combined to bring the world a line of pipes like no other.

by Chuck Stanion

*(Ardor pipes are well known for creativity of texture (as seen in the pipes Mau) as well as skilled carvings of animals and people.)

Italy is filled with wonderful people and history and customs and sights, and you should go there to see for yourself at your earliest opportunity. The landscapes make your heart and eyes grow large... lakes and mountains and seas of indefinable colors fill the world, contrasting with a sky that hangs blue and crisp and almost touchable over the cities and countryside-unless it's raining, of course; then the sky sits on your head like a cold wet sponge. But on good days it is most romantic and picturesque.

The Lake Como area, home of Ardor Pipes, is especially breathtaking. The lake reflects the surrounding hillsides, which are striated with narrow winding streets filled with small cars going way too fast in way too many directions. Yes, Italy can make you appreciate life, especially if you do much driving.

Though the traffic on the Italian streets is adrenaline inducing, the architecture of the buildings that line them is soothing. The homes are inviting, as are the businesses. Small family-owned shops, rather than malls and superstores, are the norm.

One such enterprise is Ardor, a company created by the Rovera family, which now has four generations of pipe-crafting experience.

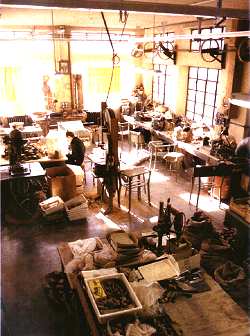

The building is large and angular, and houses living quarters for the family, the pipe factory itself, and a retail shop that sells not only pipes, but woodcrafts of all sorts: chess sets, walking sticks, jewelry boxes and various accessories. The pipes, though, are the main attraction.

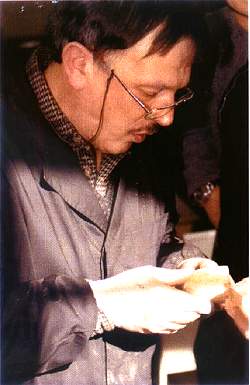

Dorelio Rovera (pictured above), is a

third-generation carver and

administrator of Ardor pipes.

Dorelio Rovera is the creative force behind Ardor pipes. He is a man in his 50s, with a carefree style and somewhat disheveled appearance, though that casual attitude ends where his pipes are concerned. When he examines a pipe, he scrutinizes the lines, the balance, the symmetry and overall workmanship. Like any sculptor, he is minutely aware of every nuance of shape. And above all else, he is his own worst critic. "Every pipe must be perfect," he says through his son Damiano, who translates his Italian into English. "I will not have my name and reputation on a pipe that is less."

Damiano Rovera, fourth-generation carver, is quickly becoming a skilled craftsman under his father's tutelage.

Damiano is also a pipemaker and, as such, represents the fourth generation of carvers in the Rovera family. In his mid-20s, Damiano claims he is merely in an apprentice stage of his carving career, though his pipes clearly show the sophistication of many years of experience. He started working with his father in the shop at age 18, though he left for a time to pursue a degree in accounting. "But I never loved it like I love pipes," he says. "And I always knew I wanted to work with my father. So now I am learning to be a pipemaker."

The two Roveras make an excellent team. Damiano's considerable skills and artistic vision sharpen more and more under the tutelage of his father; Dorelio's vast experience and unremitting perfectionism are challenged to even higher levels as he teaches his son. They learn from each other, and Ardor pipes reap the benefits of the collaboration.

This has happened before, by the way. Damiano is now learning from Dorelio, who learned from his father, Angelo, who learned the craft after his own father, Francesco Rovera, who helped start the company that would become Ardor Pipes.

Francesco Rovera was one of four brothers who joined together and started the pipe factory in Varese, Italy, making pipes that were sold throughout Europe under the Rovera name. The philosophy of the firm was somewhat different back then, with quantity of production given more emphasis than currently. Those pipes, dating back to 1911, were machine-made on equipment driven by water power.

Today the equipment is electrically powered, but even with that manufacturing advantage, the pipes are much less numerous, because each Ardor pipe is handmade to the highest individual quality. But it was a difficult evolution from the machine-made Rovera pipes to handmade Ardors.

The company's decision to change from mass-produced to handmade pipes was not easy to make, though it was arguably the best thing that could have happened. It was Dorelio who first concluded that high quality should be the defining characteristic of his family's products.

His father, Angelo, who was incredibly skilled at hand-sculpting pipes in the likeness of any person or animal he wished, felt that the machine-made production would be more likely to maintain profitability. But Dorelio, with his perfectionist's spirit, felt that reduced numbers and increased quality should be the defining direction for the company.

Angelo agreed that Dorelio's strategy could be tried. That sounds like a simple decision, but quality does not happen with a snap. Dorelio had been working since the age of 13 with his father, gradually getting better and better at his art. The father and son team had worked for years together toward the perfection that would become synonymous with the name Ardor, and Dorelio's Fatta a Mano (handmade) pipes had proved their considerable superiority before the shift in the company's philosophy could be considered.

But at last they were ready, and Dorelio and Angelo decided a new name was required to herald the shift in manufacturing. They combined their initials-Ar (Angelo Rovera) and dor (Dorelio) Rovera) together became Ardor, and the Ardor Pipe Company was christened. The meaning of the word was not lost on the team. It is a word that designates a fiery intensity of emotion, enthusiasm and devotion. "We are passionate about our pipes," says Dorelio. "Making pipes is scientific, yes. Precise engineering is required. But just as important is the emotion."

Both of those qualities are evident in

abundance. "My father can solve any problem," says Damiano. As that statement is translated for Dorelio, he shakes his head. "No," he says, "some things, are just impossible."

"All right," continues Damiano, "he can solve any problem within reason, then. I am always learning from him-I learn from him every day. He can show me why a pipe I am making has become different from the original design. He can solve problems I might have with the drilling of the pipe. He shows me how to make a design work better. I still make many mistakes."

The fish is one of Dorelio's creations

(Continue to PAGE 2 of the article)

(Return to the Ardor Home Page)