Prodigal

Son

By

Stephen A. Ross

After

exploring a career

outside of pipemaking, Damiano

Rovera joins the family business, marking the Roveras'

fourth generation as pipemakers

As a young man, Damiano Rovera sought a way to earn a living outside of the family business, Ardor Pipe Co. He attended school in England with plans to become an accountant before, like the biblical prodigal son, he discovered he wanted to become a pipemaker after all.

In his mid-30s, Damiano possesses the easygoing self-assuredness that seems to be an Italian birthright. A gifted athlete, Damiano played on a semi-pro basketball team until family and work obligations conspired with reaching the wrong side of 30, making him retire from active competition, One of the nicest people anyone could ever meet, Damiano approaches lift with an active curiosity, a willingness to confront any problem with the attitude that it can be solved and the ability to keep a smile on his face. Perhaps his demeanor can be attributed to the beauty of the Italian Lake District, where his home is nestled in the Alps' foothills. Or perhaps it stems from the realization that he made the right decision to return to Ardor.

Damiano works with his father, Dorelio Rovera, in the bottom-floor workshop of Dorelio's house, which also includes a small retail space. Working in the back corner of the spacious and bright workshop, the elder Rovera is working on a custom pipe, which the customer asked to be made with an alligator or crocodile motif. Dorelio uses a small handheld circular saw to make the detailed cuts, which include the beast's teeth, eyes and scales. After completing each little detail, he stops and shows his son, a humorous gleam in his eye, displaying an obvious enjoyment of his work. They then discuss the pipe that Damiano is creating.

Damiano describes to Dorelio what he is doing. Dorelio only offers his opinion after Damiano asks for it. They discuss the pipe's lines as Dorelio makes sweeping gestures with his hands to accentuate a point he is making. Damiano nods, thanks his father and the two men go back to work at their individual stations.

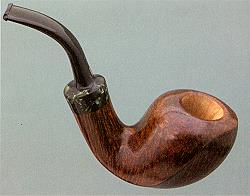

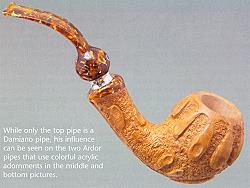

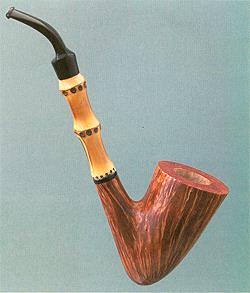

When you work with your father, there's always a kind of respect for each other," Damiano explains. "When I do something, I like to show him and have him comment on my work. Following his advice, I modify my ideas a little. But then, it works two ways. I have influenced him in a big way. He loves the classics a lot, but when he sees me mix the classic shapes with unusual colors, he experiments some himself. ,The result is that his pipes' designs have become a little freer. We help each other as we work through new ideas."

The collegial relationship between father and son has been a factor in the Rovera family's history as pipemakers, which is approaching its 100th anniversary.

In 1911, four Rovera brothers—Frederico, Carlo, Cornelio and Franscesco—established a pipe factory in Varese, selling machine-made pipes that bore the family name throughout Europe. The family continued to produce inexpensive pipes until the 1960s, when Dorelio became more involved in the company.

At 61 years old and with a slightly disheveled appearance, Dorelio says the only toys he had to play with as a child were pipe related. Speaking Italian with Damiano translating, Dorelio states that he desired nothing more than to become a pipemaker.

Starting work in the factory at 13, he saw the switch in post-war Italian manufacturing from producing inexpensive products to products famed for their quality and, often expensive, characteristics. "Made in Italy" became synonymous with high quality and high fashion as Italian companies such as Ferrari, Gucchi, Armani and Versace won accolades around the world.

"If Italian automobiles, clothing and accessories could gain worldwide respect, why not Italian smoking pipes?" Dorelio and other post-war Italian pipemakers reasoned.

Dorelio struggled to convince his father, Angelo, to make the switch from mass-produced machine-made pipes to Grafting pipes by hand. While Angelo was a talented carver who made figural pipes representing famous people and animals, he recognized that he and his son would have to prove the superiority of handmade pipes before they could justify a change in the company's philosophy.

A combination of their initials— Ar (Angelo Rovera) and Dor (Dorelio Rovera)—the Ardor Pipe Co. soon gained a reputation for creating pipes that displayed the qualities that Angelo demanded—fine smoking characteristics and fluid lines—with vigorous attention to detail and a willingness to expand each pipemaker's talents.

By the late '90s, Ardor had established its reputation, and Damiano had joined the company, performing rudimentary pipemaking tasks as he learned the craft, with Angelo and Dorelio finishing the pipes. Damiano took on more responsibilities following Angelo's death in 1999. He had learned the steps and began making complete Ardor pipes. While he still makes Ardor pipes, Damiano has now established his own pipes, which are marked with a silver "D" logo on the mouthpiece and stamped with his name.

The very fact that Dorelio allowed his son to make pipes under his own name should say something about the quality of Damiano's craftsmanship, Thanks to the Rovera family's strict requirements, Ardor has been recognized as a producer of pipes that present excellent value.

(Continue to PAGE 2 of the article)

(Return to the Ardor Home Page)